Laying the Groundwork for a Class Alignment Labor Strategy (COMPLETE)

By Daniel C, Louisville DSA; Lyra S, Chicago DSA; Sumter A, Atlanta DSA

October 25th, 2025

The following is the complete text of an article on the Class Alignment Strategy, which recently ran on this blog as a four-part series. If you would like to read the series as originally published, start with the first part here. The position articulated here is not Groundwork’s official stance as of now, but it will be put forward at the caucus convening in early 2026 for a membership vote. - Ed.

Part 1: Theory & Terrain

The authors of this piece, as labor organizers, rank-and-file union members, and historians of the labor movement, have noted a need for a new labor strategy, a Class Alignment Strategy. A strategy that explicitly defines DSA’s points of leverage and considers conjunctural factors before utilizing them will aid in rebuilding the labor movement as a whole and will harness DSA’s unique organizational strengths to align the union movement into a left-labor bloc capable of contesting power. This piece serves as an introduction to the Class Alignment strategy, which the authors intend to propose as Groundwork’s official labor strategy at the 2026 caucus convening. We view this as a priority because the presence or absence of militant, democratic, left-wing class struggle unions can fundamentally shift the balance of forces in the ongoing war of position against the capitalist class, not just on the shop floor, but in the electoral arena and in the streets.

While this article will lay out the theoretical basis for the Class Alignment Strategy at length, the authors would like to foreground the immediate tasks it perceives in DSA’s labor work. First, the sorting of membership on a chapter-by-chapter level into Labor Circles based on industry. Second, the creation of nationwide rank-and-file networks for active organizers on an industry-by-industry basis, based on the nationwide Amazon salt network. Third, the creation of DSA-member “sections” for internal organizing on a union-by-union basis. Fourth, greater coordination between chapter-level and national-level labor and electoral bodies, with the goal of harmonizing our labor and electoral work.

These modifications to DSA’s labor institutions are to be made with the short-term goals of internally organizing within our unions to politicize them, to push for investment in new organizing, aligning multiracial public sector unions like SEIU and AFSCME, and creating municipal left-labor blocs based on the model provided by the DSA-LA-UNITE-HERE-UTLA alliance in Los Angeles. However, for any of these changes to move forward, there will need to be significant increases in capacity at the NLC level, which can only be provided by cross-caucus investment in its structures and by hiring new staff.

Theoretical Orientation

This Class Alignment Strategy aims to move beyond pre-2016 DSA’s narrow permeationist strategy, Bread and Roses’s Orthodox Rank and File Strategy, and the everything and the kitchen sink “multifaceted” labor strategy offered by the Collective Power Network. It also attempts to provide an alternative to the Partyist Labor Strategy proposed by Marxist Unity Group, which correctly identifies problems with the rank and file strategy, but falls short of solving them through both a rejection of seizing executive power in the short term and an overemphasis on socialist propagandizing on the shop floor.

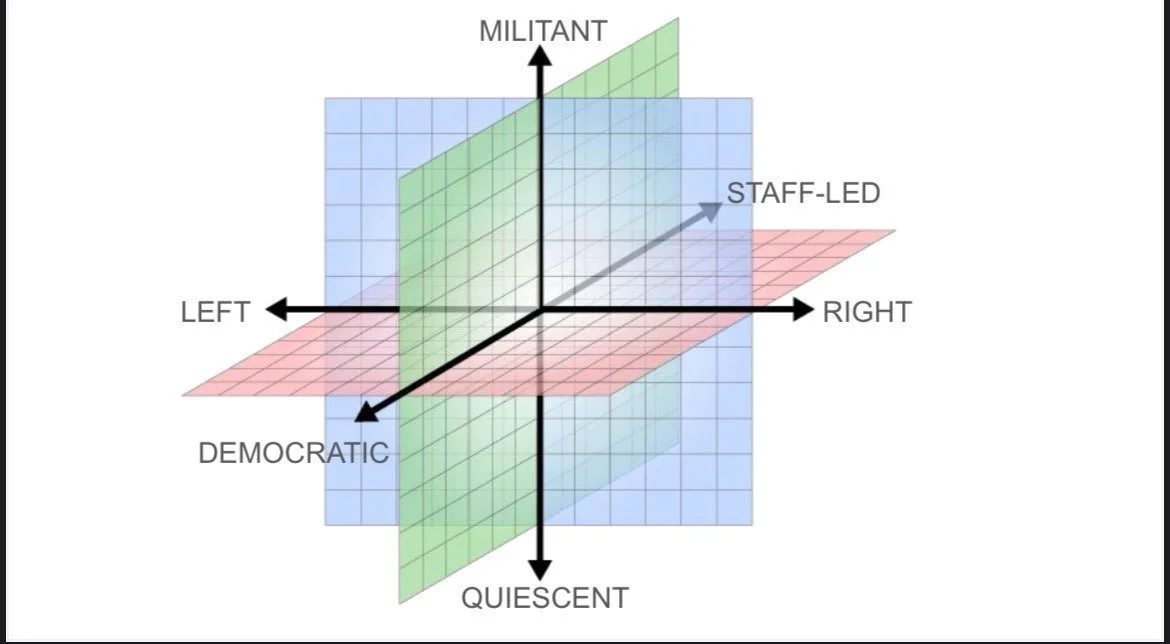

The Class Alignment Strategy relies on the process of moving unions (as groups of workers and as institutions) towards opposition to the dominant hegemonic bloc and membership in a left-labor coalition affiliated with DSA. This Left-Labor coalition will be the motive force behind a durable popular-democratic mass movement for a social transformation. Once aligned, a union can be counted on to be on our side of the balance of forces when we confront capital on the shop floors, in the streets, and at the ballot box. What aligning a union might look like depends on a variety of factors, but generally speaking, unions in the United States under the Taft-Hartley labor paradigm can be divided along three main axes:

Axis One: Militant vs Quiescent

A militant union is a union that is willing to walk up the ladder of escalation to majority strikes that will fundamentally transform a member’s life by winning demands that provide security and dignity. Militant unions invest aggressively in new organizing, and the most militant unions are willing to break the Taft-Hartley labor paradigm by engaging in open illegal strikes in defiance of injunctions, risking state repression. A quiescent union is a “dues collection agency” more concerned with maintaining the smooth flow of production than winning for its members. No union is an ideal example of either of these types; however, examples of more militant unions include red-state teachers' unions that engage in wildcat strikes in opposition to state law, many Teamsters locals, and SEIU 1199 NE. Examples of more quiescent unions would be UFCW at Kroger and SEIU’s massive home care locals.

The Rank-and-File Strategy, as it currently exists, has been successful at forming reform caucuses that pull unions towards the militant end of this axis. Shop floor militants from Solidarity, the IS (International Socialists), and later Bread and Roses have played a vital part in the creation of UAW-D and TDU, caucuses explicitly devoted to more militant and democratic unions.

Axis Two: Democratic vs Top-Down

Another important axis within the labor movement is democratic unions vs top-down unions. Democratic unions are characterized by direct election of leadership, openly ideological internal caucuses, large open directly-elected bargaining committees, and open books. Top-down unions are characterized by decision-making power residing with unelected staff and/or entrenched, self-selected leadership, multiple layers of abstraction between the rank-and-file and top leadership, closed-door bargaining, and closed books.

However, neither internal democracy nor militancy is enough to guarantee alignment with a broader socialist political project. The Teamsters have contested direct internal elections, go on strike often, and maintain a militant oppositional orientation towards management, but Sean O'Brien gives millions to Republican candidates, throws immigrants and trans people under the bus, and has aligned against the left-populist anti-oligarchy movement. There is a step beyond militant democratic unions, the project of bringing those unions into a united front to achieve a broad-based anti-imperialist social democratic transformation.

This brings us to the final axis.

Axis Three: Left vs Right

Some unions are left-wing, while others are right-wing. Anyone who has experience with teachers’ unions writ large on one end and the building trades writ large on the other is aware of this. The political orientation of unions rests on the demographics of their membership, the orientation of the institutions that can grant them contracts, and the positions of their leadership.

In this paradigm, at the center is a partisan divide between Red and Blue in the United States, with labor liberalism comprising a broad center-left in the union movement and a tacit pro-Republican workerism making up the center-right. However, our goal is to pull unions far to the left, past labor liberalism, towards alignment with DSA.

Left-wing alignment is harder to measure and to quantify than militancy and internal democracy, as aligned left unions can take a variety of forms and degrees. An ideal left-aligned union would be one with an extensive DSA presence in the rank and file and staff, characterized by close and comradely collaboration between union leadership and local DSA leadership, with a consistent track record of cross-endorsing and throwing its resources behind DSA candidates and issues. These unions are sometimes, but not always, explicitly socialist, and they often include demands in their contracts that relate to broader struggles and achieve wins for the working class as a whole. Additionally, these unions aggressively engage in new organizing that might not immediately result in new members in their core sectors. For example, SEIU 1199NE organizing tenants, or the United Electrical Workers partnering with EWOC and Southern Workers for Justice.

Part 2: Tasks & Reflection

The Task

Given these axes, a socialist’s goal should be to make existing unions more militant, more democratic, and more left. To get them to fight for better contracts with more radical demands, to directly elect their leaders, and to align as closely as possible with the party. This is part of a wider process of Class Alignment. Unfortunately, there’s the question of what to prioritize with limited resources, and what to do if our goals are occasionally contradictory. What should the party do if democratic reforms don’t immediately lead to more left-wing leadership? What if a militant union is led by a cadre of disciplined staff organizers who are seeking an alliance? What should DSA do if a closely aligned left-wing union is accepting bad contracts or falling into the hands of a self-selecting leadership? While the answers to these questions may all differ according to the local balance of forces, ongoing campaigns, and the relative value of the DSA’s relationship with each union, without a cohesive set of principles from which to answer these questions, we are bound to act indecisively and inconsistently.

So far, our efforts have been focused on making unions more militant and more democratic; it is clear that making unions more militant and democratic does not automatically lead to more left-wing unions.

What has been done

For most of our organization’s recent history, only one framework has provided answers to our previous questions. The Rank-and-File Strategy (RnFS) is an orientation towards labor that prioritizes the identification and development of a militant minority of shop floor organizers as an independent locus of power from labor leadership and bureaucracy. This is to be accomplished by continuing the industrialization tactics of the 1980s through the purposeful recruitment of socialists into strategic sectors, including education, logistics, and nursing.

To give the Rank-and-File Strategy and its adherents credit, through disciplined stewardship of the NLC, the development of an industrial YDSA to Strategic Sector pipeline, and investment in the Rank & File Project outside of DSA, they have been able to build powerful militant, democratic reform caucuses and maintain influence within those caucuses in both the Teamsters and the United Auto Workers, while simultaneously building a bench of disciplined socialists in urban teachers’ unions around the country. Through a protracted campaign of internal reform in both the Teamsters and the UAW, a completely corrupt, captured, and discredited leadership has been routed by insurgent democratic workers’ movements. The Teamsters have adopted “One Member, One Vote,” and invested in organizing Amazon. The UAW has elected a president who openly says “eat the rich,” and its graduate student locals have aligned decisively with insurgent left-wing electoral campaigns and student protest movements against imperialism.

Hitting the Wall

However, the Rank-and-File Strategy has not proven itself capable of moving beyond the demand for more militant and democratic unions towards bringing those unions on board for a project of social transformation. While the UAW’s new leadership is a definite qualitative improvement, triangulation around tariffs shows room for improvement, and Sean O’Brien’s dramatic betrayals of working-class solidarity through aligning with both reactionary forces in the Democratic party and the Republicans has disorganized our forces with anti-immigrant rhetoric and thrown a wrench into the project of creating a left-labor bloc.

There is a limit to what militant shop floor organizing centered on better contracts and a more democratic union can achieve on its own. The limitations of shop floor organizing divorced from socialist politics are best articulated by this passage in Vladimir Lenin’s What Is To Be Done:

“The question arises, what should political education consist of? Can it be confined to the propaganda of working-class hostility to the autocracy? Of course not. It is not enough to explain to the workers that they are politically oppressed (any more than it is to explain to them that their interests are antagonistic to the interests of the employers). Agitation must be conducted with regard to every concrete example of this oppression (as we have begun to carry on agitation around concrete examples of economic oppression). Inasmuch as this oppression affects the most diverse classes of society, inasmuch as it manifests itself in the most varied spheres of life and activity — vocational, civic, personal, family, religious, scientific, etc., etc. — is it not evident that we shall not be fulfilling our task of developing the political consciousness of the workers if we do not undertake the organisation of the political exposure of the autocracy in all its aspects? In order to carry on agitation around concrete instances of oppression, these instances must be exposed (as it is necessary to expose factory abuses in order to carry on economic agitation).”

In this passage, Lenin articulates one of the key shortcomings of the RnFS, which is its lack of politicization of workers, outside of the narrow demands of conditions on the shop floor, and its failure to connect rank-and-file shop floor organizers to leftist politics. Because of this, the Rank-and-file Strategy hits a wall; it cannot itself answer the question of what to do when a militant union refuses to move left or democratize. It cannot answer that question because it requires a move away from political agnosticism and towards engagement with vectors of influence outside the shop floor. Developed in a period when left-wing formations were limited to a constellation of sects, the Rank-and-File Strategy does not envision the role of a party surrogate, the state, and staff in bringing a union into alignment. Damningly, the Rank-and-File Strategy leaves power on the table.

Attempts to bridge the gap – through organizing the unorganized and by establishing informal industrial sections within the NLC – have fallen short, either due to haphazard planning or inadequate investment. EWOC, a joint DSA-UE project, has proven moderately successful in reaching and training new layers of workplace activists to organize new workplaces; however, it has not resulted in the major groundswell of union activity and membership density needed to turn the tide. Labor scholars and journalists have noted that it will require significant investment from existing unions – the only institutions capable of marshalling the necessary resources and experience – to increase union density meaningfully.

On the other hand, DSA’s sporadic attempts at industrial sections have hit barrier after barrier, including the most difficult of them all – asking more of already-taxed organizers. Valiant but short-lived efforts to connect postal workers, restaurant workers, public school educators, and other DSA members in unions have ultimately petered out, without sustained attention from organizers or a compelling campaign plan. It is challenging to determine the contours of such a unified campaign across varied unions, state legal codes, workplace conditions, and political terrains. Attempts to provide mentorship to or connect DSA members, even those working in “strategic industries,” have had limited success; therefore, the Rank-and-File Strategy has seen uneven development across states and unions. For example, the NEA still lacks a coherent rank-and-file caucus at the national level or a network of caucuses at the local level. The best approximation is UCORE, which persists completely independently of DSA. Volunteer-led efforts have thus fallen short of cohering a true DSA-led effort to analyze our unions and propose policy reforms, as well as organized efforts to change our unions.

Part 3: Vectors & Through-Lines

Vectors of Influence:

So, how do we as socialists align unions and bring them into the left-labor bloc? First, we need to survey our points of influence over union policy, then determine how to best utilize those points of influence according to our current circumstances. As it stands, there are four main points of leverage we can use to make unions more militant, democratic, and left-wing.

1st: Members

The rank-and-file members must be central to any change in a union’s alignment since, as discussed earlier, insurgent movements of rank-and-file union members are the most significant point of leverage for making unions more militant and democratic. Rank-and-file members control the strike weapon, can give and take away a union leadership’s legitimacy (and ideally their positions), and provide the constituency from which we intend to grow a left-labor political base. The rank-and-file tactic should be the most important, but not the sole component of a wider Class Alignment Strategy. To be clear, when we say “most important,” we mean it. One of our movement’s defining goals is developing the political protagonism of the working class through struggle. We believe workers need to beat their boss to believe that we can beat the bosses as a class. The rank-and-file tactic is essential to unleash strikes, not only for better working conditions and to resolve grievances, but also to develop workers’ self-confidence, experience with democracy, and political consciousness. The vast majority of DSA members involved with the labor movement should be rank-and-file members, and engagement with the organic demands and desires of rank-and-file members is a prerequisite to organizing any change whatsoever within a union.

It is members who are the most useful at moving a union in a positive direction along any of the previously listed axes. While a cadre of staff organizers can make a union more militant, more left-wing, and even more democratic through representing the organic desires of the membership more effectively, the changes that they carry out will not be as effective, lasting, or as broad-based as a transformation from below. We reject permeationism because it is a shortcut that does not involve the vast majority of the membership in the educational process of transforming their own union or developing its politics. We believe everyone is a legislator and everyone is an organizer. We believe that, whenever possible, ordinary people should be shown that they can transform the world. The best place to start is their own union.

2nd: Staff

Second to the membership, but still very influential, is a union’s staff. The role of staff can vary from union to union, but typically, staffers assist with bargaining contracts, conduct recruitment drives, represent workers in employer disputes, develop leaders, and support political efforts. In democratic unions, staff supercharge member-designed and driven campaigns through their expertise, hours on the job, and organizing connections. In undemocratic unions, staff make vital political, personnel, and bargaining decisions without the input or oversight of membership. Staffers are often members’ first contact with their union and have a fair amount of autonomy when it comes to organizing their turf.

Socialists have a key role to play as staff within the labor movement. In an ideal scenario, socialist staffers can help bolster workplace democracy. They can empower members to be the decision-makers on the shop floor and to take collective action. They can teach workers how to hold effective meetings in which democratic decision-making can happen. Socialist staffers can foster an environment of member-to-member organizing, providing rank-and-file members with the training to sign up their coworkers, represent them in labor disputes, and move their coworkers to collective action against their boss. Socialist staffers can also connect these workers’ struggles to the history of the broader socialist and labor movement, and provide key material context for their struggles.

While socialist staffers can provide this important context, it is DSA members in particular who can connect workers to current political struggles happening outside of the shop floor. This is especially true for ongoing chapter work that might be of particular interest to that worker’s segment of the working class. For instance, migrant workers or their family members might take interest in a chapter’s anti-ICE work, or a queer-heavy workforce might take interest in trans rights and bodily autonomy work. Many times, these issues overlap directly with shop floor issues. In Chicago DSA, INA staffers have been able to connect nurses they represent to the chapter's efforts to restore gender-affirming care to minors. This is an issue that directly affects INA nurses in terms of how their labor is allocated, as well as the patients they care for. INA workers getting involved with Chicago DSA’s gender-affirming care campaign helps amplify the plight of these workers and adds much-needed volunteer capacity to the campaign.

A socialist staffer’s role in an undemocratic union becomes trickier. While a staffer in an undemocratic union may have more say over campaigns and resources, situations might arise when the will of the members is in direct contrast to the actions of leadership. Socialist staffers are often closest to membership and hear their concerns daily. In a union where leadership often acts in opposition to members’ wants and needs, this can put socialist staffers in a difficult situation. In the past, DSA labor thinkers have suggested that staff can do nothing in these situations, and that it’s up to the workers themselves to address these grievances through democratic means. Although this would be ideal, some unions have truly flawed democracies, making it hard to hold unions accountable through democratic means, especially if there isn’t an ongoing rank-and-file reform effort within that union.

This was the case with the UAW, where federal intervention caused by corrupt leadership led the union to implement “one member, one vote.” In undemocratic unions, there is no culture of collective decision-making, no real efforts for member-to-member organizing, and all decisions are made apart from the rank and file. In these types of unions, workers often view their union as a service provider, and much like other service providers workers dislike, they stop paying for it and abstain from participation in the union as a political space. When workers do not perceive their union as something they collectively own, this plays right into the hands of corrupt leadership. So what is a socialist staffer to do in this situation?

In undemocratic unions, the role of a socialist staffer is especially significant; it is up to the workers of the union and their staff union to echo and amplify demands they are hearing from the rank and file. Just as we wish to guide unions in general away from a narrow economistic understanding of power, staff unions must go beyond just asking for better wages and working conditions for their organizers and leverage their power to democratize and radicalize their unions. It’s also up to these staffers to create democratic structures where they don't exist, and it is even more vital for them to train and empower the rank and file to take initiative. Socialist staffers can provide an alternative to the typical service model workers are accustomed to, and empower workers to take their collective liberation into their own hands. Although staffers shouldn’t be openly involved in organizing reform caucuses, they can lay the groundwork for the environment and conditions that would allow such a caucus to form. In more top-down, but left-wing unions, staff can pitch DSA campaigns and initiatives to both membership and leaders, and make appeals to get resourcing behind our initiatives and campaigns. In both democratic and undemocratic unions, staff are a vital point of influence that we would be foolish to ignore.

3rd: State

The state dispenses contracts, sets the terms of struggle on which labor and capital fight, and arbitrates disputes. Currently, there are many laws at the federal, state, and local levels that weaken labor power, restrict labor’s militancy, and limit the movement's ability to grow and participate in political struggle. Right-to-work laws, the ban on secondary strikes and boycotts, captive audience meetings, low fines for violating labor laws, and an overly burdensome election process are all barriers that can only be overcome by contesting and winning state power, or through winning concessions from the state via campaigns. DSA chapters should seek to win reforms that shift the terrain of worker struggle away from the boss and towards workers. These reforms could include passing the PRO Act, overturning right-to-work laws, providing unemployment pay for striking workers, or moving toward sectoral bargaining.

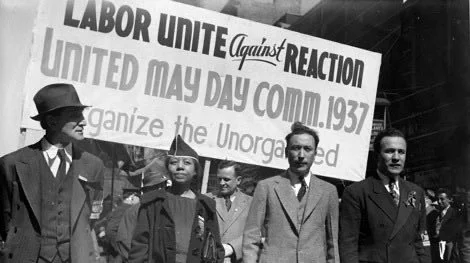

In the long term, we intend to remake the state’s relationship with organized labor. Rather than considering organized labor as one of many interest groups to which the state should respond, we aim to revive the claims made by the radical unions of the 1930s and 1940s to represent the interests of society as a whole. To achieve this, we must roll back federal Taft-Hartley regulations that ban political, sympathy, and solidarity strikes, as well as end carveouts that prevent the unionization of foremen, lower-level managers, agricultural, and domestic employees. Federal government intervention in the form of the National War Labor Board, the Fair Employment Practices Committee, and the Wagner Act-era NLRB were all vital preconditions for the largest upsurge in union density in American history. Vital personal and institutional linkages existed between state labor agencies and the radical left of the labor movement; we must restore those linkages and rebuild the state’s ability and capacity to intervene in favor of the working class.

Given the state's crucial role in setting the terrain of struggle between worker and boss, our electoral strategy should not be thought of as separate from our labor strategy. When contesting state power, it is essential that we further align the labor and socialist movements, rather than viewing them as distinct. In Chicago, a left-labor coalition with DSA in a subordinate role carried Brandon Johnson to victory. However, without socialists leading it, the coalition lacked a unified political vision and a truly mass working-class base behind it, as seen in Zohran and NYC-DSA. Chicago shows us that labor within the US, divorced from a socialist movement, isn’t cohesive enough on its own to effectively wield power. A relationship between DSA and labor can be mutually beneficial. DSA can provide political vision and an army of mobilized seasoned volunteers, while labor can provide financial resources and volunteers from the elements of the multiracial working class that we have not yet systematically recruited. By working with labor to run socialist candidates, we can help cohere and align the labor movement behind a broad-based working-class agenda that reaches beyond the trade union consciousness of each individual union.

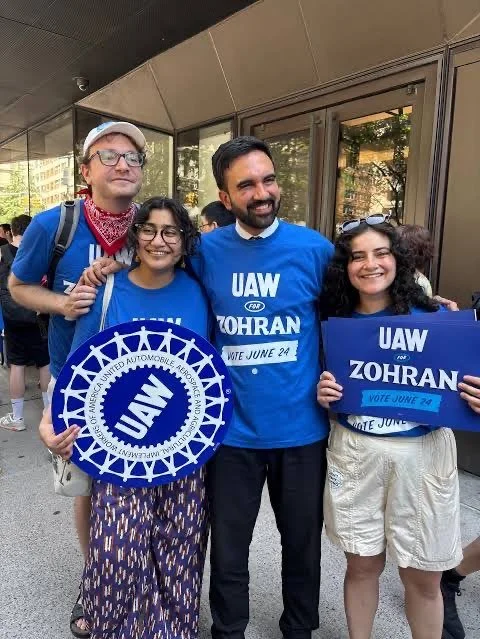

Running candidates with labor’s backing isn’t the only way to align the labor and socialist movements. Sometimes, running effective campaigns that win elections can bring unions into alignment. The vacillations of SEIU Local 1199 in New York, which shifted from endorsing Cuomo in the primary to Zohran in the general, show that the credible threat of contesting state power forces labor unions to realign towards socialist priorities and allows progressive forces within existing unions room to maneuver. Another way to move towards alignment is for DSA members within a union to organize internally to get their union to back socialist candidates and causes. The most recent example of this was NYC-DSA members within the UAW engaging in internal organizing to get the UAW to support Zohran in the primary.

In summary, we should utilize state power through contracts, access, and labor law to incentivize the alignment of labor unions with the socialist project. We should also leverage union power in the form of its membership and financial resources to support both socialist electoral campaigns and issues, as well as to recruit socialist candidates. This mutually reinforcing positive feedback loop is a vital component of the Class Alignment Strategy.

4th: New Organizing

In the 1930s, the American Federation of Labor did not charter industrial sections or engage in all-out new organizing drives until the Congress of Industrial Organizations outpaced them in organizing the previously unorganized. More recently, despite their limiting labor liberalism, the new organizing undertaken by SEIU and its former compatriots in the Change to Win Federation pressured older unions into embracing new organizing and the militant democratic currents necessary to engage in it. We should purposefully seek to organize new militant, democratic, and left-wing unions through projects like the Emergency Workers Organizing Committee, and whenever possible, organize workers into existing unions that have already been brought into class alignment.

In addition to the pressure it puts on complacent unions, new organizing is a transformative process for the workers who engage in it. DSA should champion tactics that develop lifelong organizers, from strikes for recognition to escalating pre-majority actions, since militant tactics are more likely to develop skilled organizers who win and become future shop stewards and staffers. In our new organizing efforts, we should be explicitly recruiting organic leaders not just into the unionization effort, but also, if practicable, into DSA. One part of this is making it clear that EWOC is a DSA project, but even more important is ensuring that the shops and sectors we organize move to align their unions and labor federations.

Shops organized by DSA organizers, whether rank-and-file members or staffers, should not only be organized into their unions; their advanced worker-leaders should also be aligned and brought into the struggle to fight for a class-struggle orientation within their union. This is a delicate balancing act, and while the first priority should be to build a union, which is challenging enough, the additional task of joining DSA should not be abandoned. Organic leadership should not be left to develop its own orientation towards its union’s internal politics without being offered political education and a wider class struggle orientation by socialist organizers. DSA organizers should work to ensure that successful campaigns result not just in a unionized workplace, but a unionized workplace whose organic worker-leaders have joined DSA and are involved in the DSA section for their union (elaborated on later).

Through-Lines:

Now that we have a good sense of the points of leverage the socialist movement has to align the labor movement, it is essential to keep in mind several through-lines that define the current conjuncture, which should inform our choices when determining which points to leverage.

1st: The Decline of the Labor Movement

The actual influence of militant, democratic left-wing unions is dependent on the number of their members and overall union density While the current distribution of union density across the country indicates that warding off right-to-work laws, repealing them when they’re passed, and keeping union busters out of government has a positive effect on union density, we should keep the current low density and weakness of the labor movement in mind, not as an excuse not to take risks or to limit our horizon, but to encourage us, wherever we are, to ask if a labor campaign is creating more unionized workers, not just changing the orientation of existing ones.

2nd: The Left’s Historical Isolation and the Need for New Hegemonic Logic

The left has not had broad credibility in the labor movement since the Red Scare and the purge of the left-wing CIO unions. Decades of sectarian infighting and entryism have left a bad taste in the mouth of union leadership and the rank and file. However, that does not change the fact that a broad psychological shift is needed in both rank-and-file workers and union leaders, away from a defensive, economistic mindset and towards the possibility of mass redistribution and social transformation.

Only the left can effectuate that change, but it cannot do so through sloganeering and a recitation of ideological priors; we must prove that a better world is possible through deeds, not words. We must prove that, in Sara Nelson’s words, “solidarity is a muscle” that is built when we flex it; that labor is not an interest group in a zero-sum game of expending “political capital” and turf wars with “competing organizations,” but is instead a machine that builds power through concerted efforts to win. When utilizing the Class Alignment Strategy, we should consistently ask: Does this campaign articulate a socialist vision through concrete goals that are clear and accessible to the rank-and-file? Does it prove socialists can win?

3rd: Rising Fascism

Labor unions, along with every other hard-won victory for social and economic justice in the 20th century, are under assault. We should explicitly connect our defense of labor unions to our defense of America’s multiracial democracy. One of the easiest ways to articulate our differences from business unionists, labor liberals, and conservative unionists is by following in the footsteps of the Communist Party in the 1930s. We must be militantly inclusive and advance an anti-racist, industrial, feminist, pro-immigrant, and pro-trans orientation at every point of leverage. This is an orientation that is possible without alienating all but the most bigoted sectors of the unionized white working-class population, through the use of constructive politics and redirecting anger away from the marginalized and towards the billionaires, oligarchs, and hatemongers.

Uniting all these through-lines is the reality that unions will not become more left-wing simply through salting in more left-wing members and staffers, reforming labor law, and organizing new unions. Though all of these tactics will certainly help, class alignment at its core must be an organic process in the consciousness of the workers and their leaders, a process that is best abetted by socialists demonstrating that we are the most effective resistance to resurgent fascism, that we are effective in bringing millions of new workers into the labor movement, and that we are capable of governing in a way that meets labor’s needs more effectively than the Democrats.

Part 4: What Should Be Done

With these four points of leverage and three conjunctural realities in mind, the authors have developed a series of priorities for DSA’s labor work. These priorities are designed to achieve a combination of short-term and long-term goals. The short-term goals are to align unions in which DSA members already have a strong presence, to arrest the nationwide decline in union membership, and to build municipal left-labor alliances capable of passing pro-labor legislation.

The first long-term goal is for the union movement to reach “escape velocity” and for a national left-labor bloc to effect a wave of unionization similar to that of the 1930s or 1960s, enabling 21st-century unionism to become a social movement with a hegemonic valence and significance far beyond DSA’s orbit. DSA is to shepherd this social movement towards a class-struggle orientation, one that breaks the back of the Taft-Hartley consensus and articulates demands surrounding not just wages and security, but prices, hiring, and control of the shop floor, with the eventual goal of carrying out the prerogative first laid out by the United Farm Equipment workers in the 1930s, that "management has no right to exist.”

The second, more long-term goal is to create a social and legal environment where allied democratic, militant, and left-wing unions can officially affiliate with DSA, as the militant shop-floor element of a socialist party. In this configuration, union leadership would come from the rank and file and be active DSA cadre, with the goal of open strategic coordination between union leadership and local chapters, much like our approach with SIOs. These unions would have formal agreements to back socialist campaigns and priorities, and, once we have amassed sufficient leverage, conduct explicitly political strikes in favor of mass redistribution and economic democratization.

The Class Alignment Strategy recommends four modifications to DSA’s labor institutions in order to leverage our members as workers, both unionized and non-unionized.

First, the authors call for chapter labor committees to map their membership and sort them into labor circles, which are groups of DSA members organized by their employment sector. These labor circles are to encourage unionized DSA members and DSA union staffers to join their union’s DSA section (discussed later), non-unionized DSA members to organize their workplaces and join nationwide rank-and-file networks (discussed later), develop strategies to recruit workers in their sector into DSA, recommend chapter orientations towards their respective sectors and employers, as well as connect active organizers with groups like EWOC and Workers Organizing Workers.

Second, the authors call for the creation of new nationwide rank-and-file networks, organized on an industry-by-industry or target-by-target basis and comprised of DSA members actively organizing in workplaces, modeled on the recently created nationwide Amazon salt network. These rank-and-file networks will share information, determine points of leverage, and provide mutual support to ongoing unionization campaigns. These networks will discuss among themselves the most effective methods for organizing their respective industries.

Third, the authors call for unionized DSA members and DSA staffers to create “sections” within their unions. These sections are to organize within their unions to make them more militant, democratic, and left-wing. To decide which axis to prioritize at any given moment, sections will operate with a wide degree of organizational autonomy, although they will be required to maintain internal democracy based on the principle of “one member, one vote.” These sections will be given latitude to decide their orientation towards their local and international unions, and choose between supporting existing leadership in the case of an aligned union, working within a broader reform caucus, or creating an explicitly socialist caucus. Sections will be harmonized with chapter and national priorities through the creation of Socialists in Labor (SiL) committees, tasked with liaising with the sections to determine how they can support wider DSA priorities and how DSA can support them.

Fourth, the authors call for greater coordination between both chapter-level and national-level electoral and labor bodies. DSA sections should push their unions to endorse and support DSA candidates, while DSA left-labor candidates should use the bully pulpit to support unionization drives, train DSA members to be organizers, and pass pro-labor legislation. Coordination between SiL and SiO committees, as well as between labor and electoral committees, is vital to ensure that our labor and electoral priorities do not conflict. In particular, we propose a much greater degree of coordination between NLC and NEC, from leadership down to the rank-and-file. In creating an explicitly political labor strategy predicated on our ability to wield state power, it’s crucial that our best electoral and labor organizers are able to jointly discuss tactics, share best practices, keep each other up to date, and – if necessary – run truly joint external-facing campaigns.

Utilizing these new institutions and organizational forms, the authors recommend the following five-point immediate course of action:

First, the authors call for DSA Sections to organize within their unions to effectuate investment in new organizing, especially through encouraging their unions to fund and affiliate with EWOC. The great burst of unionization launched by the CIO in the 1930s was accomplished through a variety of factors, one of the most important of which was the United Mine Workers’ decision to invest tens of millions of dollars into new organizing. We believe that an even larger investment by existing unions will be necessary to set off a firestorm of new organizing. Already-aligned unions such as UNITE-HERE, UTLA, and CTU should be the first unions brought on board for this project.

Second, the authors call for prioritizing the alignment of large, multiracial public sector unions such as SEIU and AFSCME. These unions and their vast resources will provide not just inroads into demographics historically suspicious of DSA, but their alignment will also deprive the Democratic establishment of key allies. These public sector unions are to be considered strategic priorities for the class alignment strategy.

Third, the authors call for the creation of municipal left-labor blocs. These close alliances between DSA and aligned class struggle unions should co-endorse candidates, collaborate on campaigns, and jointly push for transformative non-reformist reforms. Closely aligned unions should be considered our most vital partners, and our local leadership should coordinate directly with their leadership.

Fourth, the authors call for DSA union sections to politicize their unions. Regardless of a DSA section’s decision as to whether or not to support existing leadership, a reform caucus, or form a socialist caucus, they should pressure their unions to fight back against right-wing attacks on immigrants and multiracial democracy, and endorse an arms embargo on Israel. These efforts should be coordinated with national and local DSA campaigns.

Fifth, the authors call for a DSA-wide investment in our National Labor Commission and its structures. To implement a strategy as ambitious as the Class Alignment Strategy, national labor bodies will require significantly more investment, both in volunteer and staff hours. We intend to put our words into action. If this strategy is adopted by Groundwork, we plan to put our time where our mouths are and invest in the NLC, as well as call for the hiring of labor staffers tasked with supercharging the efforts of DSA sections to align their unions.

In Summation:

The first theoretical proposition of the Class Alignment Strategy is that we utilize all of the previously listed points of leverage, to make unions more left, militant, and democratic with each leverage point being prioritized in proportion to the balance of forces in the union being considered, the immediate objectives of the chapter engaging in labor work, and the axis we are attempting to move.

The second theoretical proposition is that when prioritizing points of leverage, we factor in the through-lines that define the current conjuncture, namely: the rise of fascism, the left’s isolation from labor, and the overall decline of the labor movement. The methods we will use to carry out this alignment are Labor Circles, nationwide rank-and-file networks, and DSA union sections.

The immediate goals of the Class Alignment Strategy are to encourage already-aligned unions to contribute to EWOC, build out municipal left-labor blocs, align multiracial public sector unions such as SEIU and AFSCME, bring our unions into the fight against fascism and Zionism, and build the NLC into a body capable of coordinating this nationwide strategy.

The long-term goals of this Class Alignment Strategy are to create a militant, democratic left-wing union movement aligned with DSA and working alongside it to break the bosses’ power in the workplace, dismantle the US empire, and carry out mass redistribution towards the end goal of a fundamental social transformation.

This strategy of Class Alignment is not a purely theoretical proposition. It is already in practice in our organization’s second biggest chapter, Los Angeles. DSA Los Angeles has its leadership meetings in the United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA) skyscraper in Koreatown. One of its most recognizable SIOs is a long-term organizer with UNITE-HERE Local 11, the hotel workers’ union. DSA, UTLA, and UNITE-HERE often co-endorse the same set of candidates for office, and the members of each organization work on each other’s campaigns. The collaboration between these unions and DSA spans the level of DSA cadre taking up rank-and-file positions within the unions to coordination between leadership towards the shared goal of a “Los Angeles for the Many.” Los Angeles’s DSA-UNITE-HERE-UTLA alliance is a real-world example of a left-labor bloc rooted in the multiracial working class, a bloc that we will need to reconstitute across the country if we are going to unite labor and the left to run a socialist for President.